We’ve heard about the lovefest between blockchain tech and mobility for ages, with lots of hype around peer-to-peer (P2P) payments for autonomous vehicles, vehicle sovereignty, and car-sharing. But how does it all work and why should we care?

The most recent effort is by Car IQ . The company has developed the first payment network to allow connected cars and trucks to pay machine-to-machine (M2M) transactions. Vehicles can pay for fuel, tolls, parking, and more without a credit card.

Why use blockchain technology for in-car transactions?

Existing transactions using credit cards, debit cards, and electronic fund transactions require customer action. They are costly, difficult to reconcile, and prone to fraud.

The most significant issues of M2M payments are security and authenticity. An example is verifying the identity of a vehicle and ensuring it receives the services that it pays for.

Fleet managers, automotive manufacturers, car-sharing services, ride-sharing platforms, and commercial fleets are all at risk, as well as the service providers and payment networks.

In response, Car IQ has created a Know Your Machine identification process meaning vehicles can pay for and validate transactions. This eliminates the need for human use of credit cards to process payments.

According to Sterling Pratz, CEO of Car IQ:

What are other use cases for blockchain tech in mobility?

The twin to authenticity is transparency; machines handling data like vehicle mileage, battery charging levels and cost, and insurance details need accuracy. Otherwise, the data may be fraudulent or even tampered with by cybercriminals.

This is the gold star when it comes to autonomous vehicles (AVs), which will in the future need the ability to receive or make payments autonomously, which is the next step for payment services like those facilitated by Car IQ.

Walk me through all this again like I’m an idiot?

So, I might own an autonomous vehicle. It needs to talk to machines like traffic lights, parking meters, and other city infrastructure without any input from me.

To do so, it needs to find, authenticate, communicate and transact with those machines. If the identity of these machines is not verified, it could, for example, be connecting to a parking meter that has been hacked and can steal my car’s data.

How else are mobility companies using blockchain tech?

Daimler Mobility is working on smartVIN to stop odometer tampering in second-hand car sales. They aim to create a secure virtual vault to store vehicle information and history without being changed.

Berlin startup peaq is developing a vendor-agnostic e-charging platform where customers can charge their vehicle at any station using roaming contracts.

Blockchain tech wunderkinds IOTA have also worked with Jaguar to deploy smart wallet technology in their cars. Owners earn credits by enabling their cars to automatically report useful road condition data such as traffic congestion or potholes to navigation providers or local authorities.

Use cases are constantly evolving

This is just the beginning, in the future EVs will earn money by participating in peer-to-peer energy trading or feeding power back to the grid. Yep, you could make cash from that escooter ride.

EVs will also use V2E (vehicle-to-everything) communication. They could share traffic rerouting due to a lane closure. Cars could be alerted of an approaching emergency vehicle. A car in traffic could pay to overtake another vehicle.

You may also enjoy:

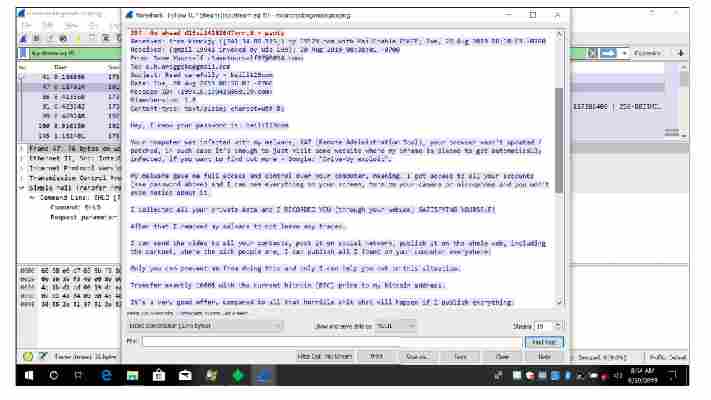

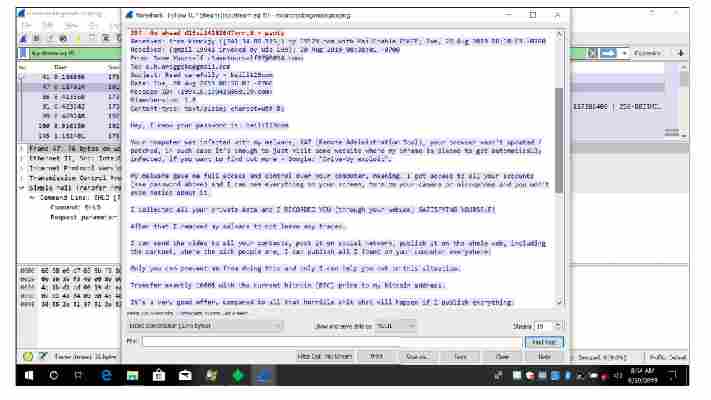

Researchers find Bitcoin sextortion malware also mines Monero

Analysts have reportedly discovered the source of the sextortion emails that’ve plagued the internet since last year — the ones that demand Bitcoin or else they’ll leak videos of you masturbating to kinky pornography.

Reason Cybersecurity researchers dubbed the malware Save Yourself , as recipients typically receive the bogus emails from senders like “ [email protected] ”

The emails state that dangerous malware has infected the recipient’s machine, but Reason found this isn’t the case.

Instead, the firm discovered the malware forcing devices to act as blackmail proxies is also secretly mining privacy-focused cryptocurrency Monero, with all funds generated going directly the attackers.

Save Yourself cleaners are spreading more malware

The firm was clear to point out that receiving the Bitcoin sextortion email doesn’t automatically mean infection, just that the recipient’s email address has been exposed in a password dump.

Researchers ironically found, however, that many sites offering products to supposedly remove the Save Yourself malware were actually peddling malware.

“It is very possible that the malware author has gathered and combined several viruses and modified them to suit their own needs,” said Reason.

To date, analysts found more than 110,000 users have been infected with the Save Yourself malware.

Save Yourself can also steal your Bitcoin

Reason reported that the malware is designed to remain under the user’s radar. In particular, Save Yourself only uses 50 percent of the infected machine’s CPU to mine Monero, so as not to raise suspicion.

The malware can also reportedly read clipboard data and replace Bitcoin wallet addresses with its own, presumably to redirect cryptocurrency transactions to the attackers.

Save Yourself is also said to compromise any executable found on the target machine to ensure automatic infection any time the user runs such files.

“The desired executable will then run as it should, so the user won’t suspect that there’s anything wrong,” said Reason. “Nor will anything look suspicious when analysing the sample since – at first glance, it will look like known software (icon, signature, strings, functionality).”

The firm noted that most anti-virus solutions should detect and clear the malware. As well, major email providers are automatically protecting users against the sextortion emails.

Hard Fork previously reported, though, that the attackers are pivoting, now demanding Litecoin instead of Bitcoin so as to dodge email filters.

Want more Hard Fork? Join us in Amsterdam on October 15-17 to discuss blockchain and cryptocurrency with leading experts.

Broke? Think long and hard before using buy-now-pay-later apps

Whether you use Klarna all the time or have barely heard of it, it’s time to start paying attention: the buy-now-pay-later app has just become the biggest private fintech company in Europe. Klarna has completed a new round of fundraising, valuing it at US$46 billion (£33 billion). That’s four times what it was worth last September , and on a par with fellow Swedish tech giant Spotify .

Klarna offers interest-free credit on purchases with participating retailers, including Decathlon, Desigual, JD Sports and Oasis. It allows shoppers to delay payment, or split larger purchases into manageable sums, and does not perform traditional credit checks, opting for a more permissive “ soft search ”. Retailers cover the cost of the interest as if it was a sales discount.

Klarna operates in western Europe, Australia and the US, and has exploded in popularity during the pandemic. It claims to have 90 million customers, including 13 million in the UK, and has numerous rivals such as Clearpay/Afterpay , Affirm and Sezzle . Traditional retailers like M&S and John Lewis are also reported to be looking at entering the fray.

Such offerings are controversial, however. Critics allege such schemes encourage overspending and can potentially ruin customers’ credit histories if they fail to keep up on payments. Many see parallels between these schemes and notorious “pay day lenders” from years gone by such as Wongaom .

Four in ten customers in the UK who have used these apps in the last 12 months are reportedly struggling to repay. A quarter of consumers reported that they regretted using these platforms, with many saying they cannot afford repayments or are spending more than they expected. Similarly, Comparethemarkeom reported earlier this year that one fifth of users couldn’t repay Christmas spending without taking on more debt.

In the UK, the concerns prompted a review published in February by Christopher Woolard, formerly of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). As a result, the FCA is now subjecting these operators to the same regulations as more traditional creditors, requiring things like affordability checks and making sure customers are treated fairly.

Some might argue that this solves the problem, but I disagree. Insights from behavioural psychology can shed light on this, and seemingly dusty debates from ancient Greek philosophy reveal why it’s wrong.

The psychological risks

Klarna claims to offer a “healthier, simpler and smarter alternative to credit cards”. It primarily targets millennials, with an average customer age of 33. Marketing material presents the app as the choice of the savvy shopper, with a clean wholesome aesthetic, reminiscent of a Scandi-style ad agency or hipster café menu.

Under FCA regulation, such lenders will be treated like other financial services targeting millennials such as Starling Bank or Monzo . So why isn’t it a case of problem solved?

By offering goods immediately, and delaying the pain of parting with any money, buy-now-pay-later lenders exploit the human tendency to undervalue future losses and overvalue present satisfaction – known as present bias. Research shows that this bias increases in response to instability and stress, raising the worry that such services disproportionately target consumers who are already vulnerable.

You could argue that credit cards also do this, but buy-now-pay-later lenders operate without hard credit checks, and go about this in an especially concerning manner. The service is offered at the online checkout, and often set by the retail partner as the default payment option . As Nobel prize-winning economists Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein argue in their influential book Nudge, altering defaults is particularly effective at changing behaviour.

Lenders primarily focus on consumer goods such as clothing and cosmetics, which are typically the subject of impulse buys. Focusing on products related to physical appearance, and targeting a particular age group, could shift social norms regarding consumption within the demographic, making higher value clothing items the norm. Once established, such norms are difficult to avoid .

These lenders also take advantage of “ loss aversion ” – the universal human tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. They do this by promoting their services as a way for online shoppers to order multiple items and then return those they don’t like. Because of the bias, shoppers may not return products once they have them at home – even if that was their original intention.

Thank you, Aristotle

One might say these strategies manipulate customers. Yet one person’s manipulation is another’s persuasion, and all commercial businesses employ persuasive strategies to encourage customers to spend.

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and his followers can help us draw a meaningful distinction between persuasion and manipulation. In a debate with the Sophists (specialists in the art of persuasion), the Aristotelians argued that the difference between manipulation and other persuasive strategies is that it bypasses or subverts the target’s rational capacities.

On that rationale, buy-now-pay-later apps are arguably manipulative as they rely on our irrational psychological biases. The concern is therefore less that they encourage us to spend, but how they do it. Some might argue that manipulation is everywhere, especially in advertising, but that doesn’t make it right. This is an ethical issue that simply classifying Klarna as a bank won’t solve.

What, then, is to be done? An outright ban would unfairly impact responsible users of the service. What is needed is regulation sensitive to the unique nature of these lenders, their service and the risks. It needs to include a duty to inform customers of the psychological biases that these services take advantage of (unwittingly or otherwise), to help consumers to make rational financial decisions. Apps would therefore need to point, for example, to the risks of consumers being tempted to keep more items once they have been bought, and the risks of default payment options.

Alongside this, we need a new professional body dedicated to overseeing this form of lending. It would need regulatory powers, and a commitment to act in the public interest enshrined in a code of conduct reflecting the unique ethical risks involved.

Article by Joshua Hobbs , Lecturer and Consultant in Applied Ethics, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .