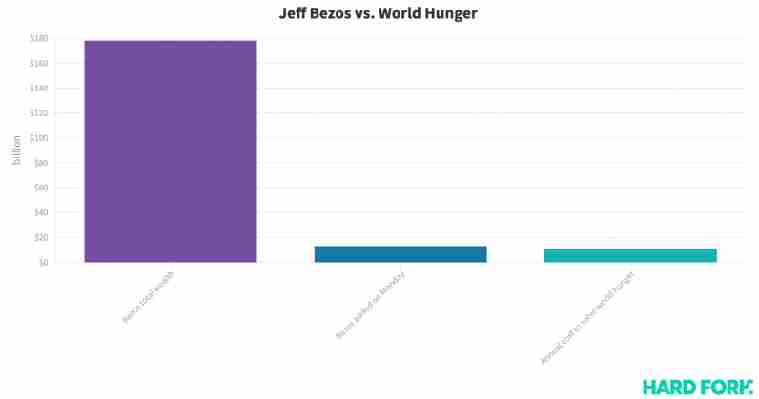

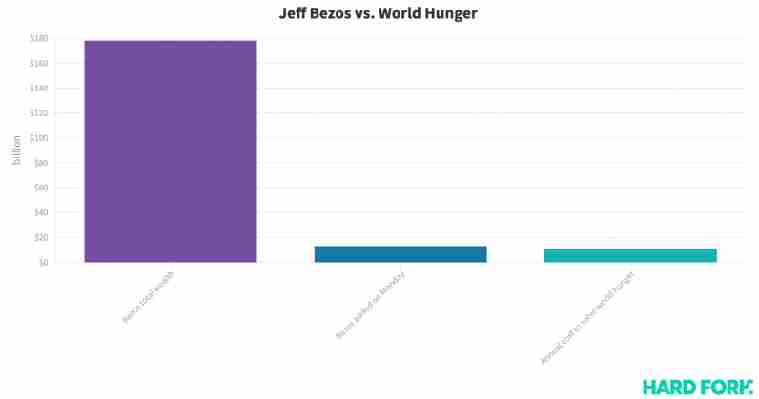

Amazon baldking Jeff Bezos added $13 billion to his net worth earlier this week, simply a stupid amount of wealth for just one person to acquire in one day — billionaire chief exec or otherwise.

And so, one Twitter account is hilariously posing a very poignant question: has Jeff Bezos decided to end world hunger?

@HasBezosDecided’s bio cites a report from the Institute of Food Policy Research Institute that found solving world hunger by 2030 would cost $11 billion in extra spending each year.

Every day, the account confirms whether Bezos has bothered to contribute what represents a small fraction of his fortune to that goal. After all, he just added $2 billion more than that to his net portfolio in a single fucking day.

Assets like Amazon stocks can be exchanged for cash

As one might expect, argument boils underneath @HasBezosDecided’s tweets. While some make the “ rich people are actually poor ” argument, others are quick to join in on the fun.

Even free market sycophants must see the absurdity of it all: Bezos was already by far the world’s richest person before Monday, and he now has a $178 billion personal fortune that the media has noted exceeds the market values of some of the world’s most prominent brands like McDonald’s and Nike.

Bezos’ wealth even puts oil behemoth Exxon Mobil’s total market value to shame.

One portfolio manager from investment fund RWC Partners Equity Income told The Guardian that Amazon’s shares have returned 199,908% since its original listing way back in 1997, making it “a manmade creation that has so far defied the laws of finance.”

And while The Guardian highlighted that Bezos has indeed given $2 billion to the Bezos Day One Fund, which works to address homelessness and boost education for children of low-income families, that contribution represented little more than 1% of his overall wealth.

[

In any case, if you were wondering if Bezos solved world hunger today: Nope. Not yet. Not tomorrow either. Sad.

How a blockchain-based digital ID system could help tackle human trafficking

Human trafficking affects every country in the world. In fact, estimates say that 20-40 million people are enslaved across the globe , earning criminals profits of approximately $150 billion a year.

The problem is unlikely to go away altogether, but what if emerging technologies such as blockchain and increased data sharing could make it harder for criminals to traffic victims and make it easier and quicker for authorities to save them?

What’s the problem?

Before we start looking at how technology can help solve the problem, it’s important to understand what human trafficking is and how criminals operate.

The term refers to the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour , commercial sexual exploitation, or sexual slavery. Victims are often lured by false promises of lucrative work, stability, education , or a loving relationship .

Although the crime spans all demographics , there are some instances or vulnerabilities that lead to increased susceptibility. For example, runaway and homeless youth, victims of domestic violence , sexual assault , war, conflict, or social discrimination are usually more heavily targeted by traffickers .

They control and manipulate these individuals by leveraging the non-portability of many work visas as well as the victims’ lack of familiarity with their surroundings, laws and rights, language fluency, and cultural understanding.

It’s often difficult for victims to get help as traffickers may confiscate their identification documents (if they have them to begin with) and money.

How can blockchain help?

Human trafficking is a complex and heartbreaking problem.

If we consider the issue from the point of view that potential victims have few resources and lack any form of identification , we can get a real sense of how blockchain can help.

We live in an increasingly digital age , and as such, the notion of every citizen having a digital ID is not so far fetched as it was several decades ago.

Imagine, for example, that someone’s virtual identity is created on a private blockchain using unique biometric information such as a fingerprint , or an eye scan.

Once this is saved on a blockchain , the information is immutable and as such can not be forged, meaning traffickers wouldn’t be able to tamper it or change a victim’s identity . A strategy often used by traffickers to get their victims across border controls.

Importantly, blockchain technology is also decentralized, meaning that the embedded data is far more secure than it would be on a centralized server .

As a borderless technology, blockchain ID documentation and tracking can take place anywhere — so long as the parties involved are able to cooperate and collaborate while pledging to input the correct data .

The industry is still nascent, but the application of blockchain in tackling social issues such as human trafficking is both feasible and sustainable.

Human trafficking is a serious issue and as such the quest for a solution must be done so responsibly. Touting blockchain’s potential simply because it’s become trendy is a huge disservice to victims but also hampers the technology’s long-term success.

Having said this, the severity of the challenge warrants all explorations and blockchain could indeed be part of the solution — but it’s important to remember it doesn’t necessarily hold all the answers.

We’ll be exploring how blockchain tech can curb child trafficking and modern-day slavery and what the challenges of doing so are at Hard Fork Summit . Join us in Amsterdam on October 15-17 to discuss blockchain and cryptocurrency with leading experts.

WWF debacle makes it clear that ‘eco-friendly’ NFTs don’t really exist

Most online images are just a right-click away from being in someone’s personal collection. They’re free, pretty much. So it’s tough for charities to fundraise with them. That is, until 2017 when non-fungible tokens , or NFTs, came along. Unlike regular pieces of digital media, NFTs can’t be so easily copied. And for as long as they have existed, there have been conservation charities using them for fundraising.

A cartoon drawing of a cat-turtle named Honu raised US$25,000 (£18,485) for ocean conservation charities in 2018. Rewilder is a non-profit organization using NFT auctions to raise funds to buy land for reforestation. The charity claims to have raised US$241,700.

There have been various cartoon apes sold for US$850,000 , with the money going to orangutan conservation charities. The most expensive NFT to date, a picture of some small grey balls, sold to multiple buyers for US$92 million in December 2021.

With many UK charities in dire straits , it’s no surprise some want a piece of the crypto action too.

Recently, WWF UK joined the NFT circus with its Tokens for Nature collection. But before the fundraiser had even started, the project sparked a backlash from environmentalists online who worried about its carbon footprint. Within just a few days, the sale was terminated .

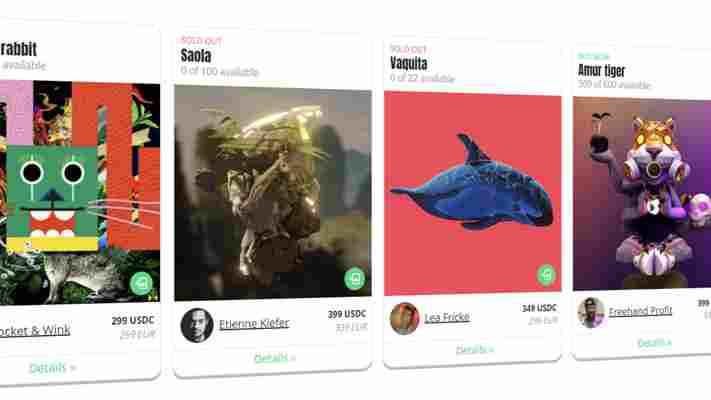

The NFAs (or Non-Fungible Animals) project aimed to raise lots of money and awareness about endangered animals. The number of rare animal images available for sale corresponded to the estimated number left in the wild. There were 290 Giant ibis NFAs, for example. An ibis jpeg would have raised about US$400 through a single sale .

‘Eco-friendly’ NFTs?

According to one estimate, NFTs generate more carbon emissions than Singapore as a result of their energy consumption.

Most NFT creators use a technology called Ethereum, which is a blockchain system similar to Bitcoin that involves an energy-intensive computer function called mining. Specialist mining computers take turns validating transactions while guessing the combination of a long string of automatically generated digits. The computer that correctly guesses the combination first wins a reward paid in a cryptocurrency called ether.

Unlike regular NFTs though, WWF claimed that its NFAs were “ eco-friendly ”. In its sustainability statement, the charity suggested the sale of all 8,000 or so NFAs would have a similar carbon footprint to a pint of milk, or a half-dozen eggs. The reason for this negligible impact they claimed was a clever blockchain application called Polygon, which would have allowed WWF’s project fewer direct interactions with the Ethereum blockchain. WWF wouldn’t then need to take as much responsibility for its share of Ethereum’s monstrous carbon footprint .

So why the Twitter tantrums?

WWF’s assumption was a tricky one. That’s because Polygon depends on Ethereum contracts to carry out essential services , such as moving assets between Ethereum and Polygon and creating checkpoints between the two. According to Alex de Vries of the cryptocurrency monitoring website, Digiconomist, the footprint of WWF’s project was actually around 2,100 times more (12,600 eggs) than the estimate provided by the charity.

There are also second-order effects to consider. Ethereum’s carbon emissions are not related directly to the number of transactions occurring on the network. PoW mining is what gives Ethereum its dirty reputation . By pumping up the hype around NFT markets, the collection could drive up the price of Ethereum. This would encourage more PoW mining, increasing the network’s overall carbon footprint.

Initial buyers of NFAs would purchase them from WWF’s dedicated website . But buyers can relist their artwork on the popular NFT marketplace, OpenSea. OpenSea is currently the number one gas guzzler on the Ethereum network, responsible for nearly 20% of actions on the blockchain.

Blockchain backlash

WWF is not the first charity to reevaluate its position on crypto-giving. In 2021, Greenpeace stopped accepting bitcoin donations after seven years. Friends of the Earth soon followed. The WWF furore forced the wildlife charity, International Animal Rescue to park its NFT fundraising plans indefinitely. Internet nonprofits Mozilla and Wikipedia have also reconsidered their crypto-giving strategies on climate change grounds.

There are multiple NFT-friendly blockchains that don’t cause carbon headaches. Even so, research shows it’s difficult for charities to fundraise using NFTs without getting their hands dirty.

Charities should be mindful of growing public disapproval of blockchain projects. Some argue that the technology is driven by predatory marketing tactics. Others claim blockchain is a platform for Ponzi schemes , grift, and multi-level marketing arrangements. According to OpenSea , 80% of the NFTs minted through its site are spam, scams, or otherwise fraudulent.

Research also shows cryptocurrencies can restrict the work of conservation charities. In 2018, WWF partnered with blockchain developers, AidChain . To improve transparency in the donor tracking process, AidChain encouraged WWF to pay their service providers in a cryptocurrency called AidCoin. Using an Ethereum smart contract, donors could then track and manage how funds were spent.

Platforms like this can allow non-expert crypto donors to encode concrete conditions to their donations. Break the conditions – lose the funds. Great for the donor. Lousy for the charity’s conservation experts.

Before reacting to crypto-giving hype, conservation charities such as WWF need to do their homework. Animal jpegs and cryptocurrencies may seem a harmless way to fundraise. But mindlessly jumping on the blockchain bandwagon could tie their hands while longstanding donors take their support elsewhere.

This article by Peter Howson , Senior Lecturer in International Development, Northumbria University, Newcastle , is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .